Dance of Death

Remember that you will die

In the midst of life -

we are surrounded by death

In this Section

By Hildegard Vogeler and Hartmut Freytag

To the dance

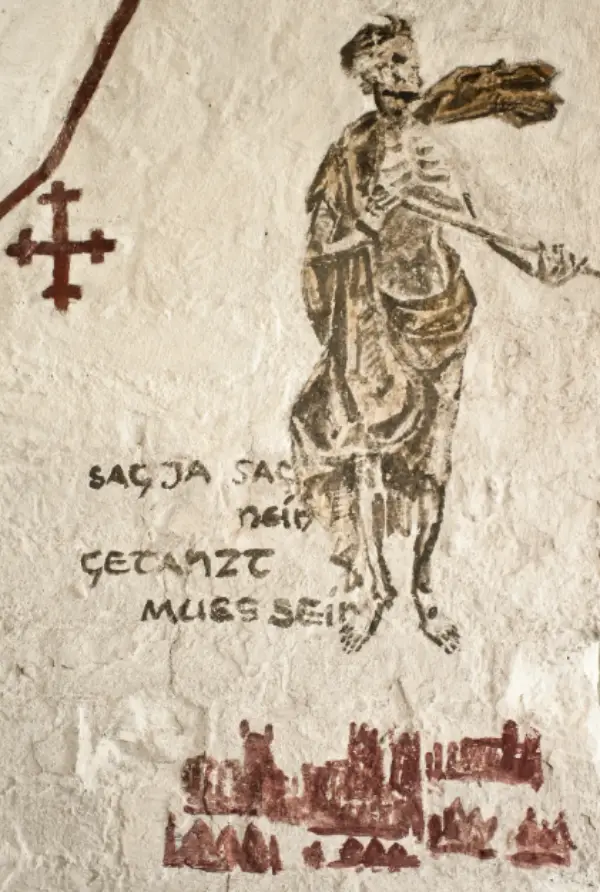

The famous Lübeck Dance of Death was created by the young Bernt Notke in 1463, modelled on the Danse Macabre in Paris from 1424/25, for the confessional chapel in the north of St Marien. This side, facing away from the light, suggests the idea of death and reminds people to live their lives in accordance with Christian teachings through repentance, confession and penance. At that time, the plague was expected to spread from the south, which it did indeed reach Lübeck at Easter 1464.

The Dance of Death was not painted on wooden panels, but on a 26-metre-long and almost 2-metre-high linen wall covering that stretched above the confessional along the walls of the chapel as a continuous sequence of images. Led by Death playing the flute and carrying a coffin, the frieze depicted 24 almost life-size couples. Each couple consisted of a figure of Death and a (still) living person, starting with the Pope and the Emperor, followed by the Mayor and the Merchant, and ending with the Farmer and the Infant. The dance included representatives of all social classes and included individual female figures and different age groups. The living joined in the dance of death only stiffly and reluctantly, while the skeletons jumped wildly and exuberantly. In the end, however, Death, wielding a scythe, mowed down all life.

The fact that this macabre dance takes place directly in front of the local landscape, with the representative city backdrop of Lübeck at its centre, distinguishes the Lübeck Dance of Death from all other traditional dances of death. This allows viewers to identify with the figures in the dance and recognise that a mirror is being held up to them here and now, in which they see themselves dancing with death. In the face of death, the transience of power, wealth and beauty in this world is thus revealed.

Just as artfully interwoven as the colourful sequence of images in the painting, the Low German text unfolded beneath the figures, depicting the dialogue between the figures of death and the living. Here, the dance of death reminded individuals to focus their lives on the hereafter and salvation on the one hand, and to commit themselves to their personal tasks within the social community in this world on the other.

The Dance of Death in St Marien has a "sister piece" in St Nicholas' Church in Tallinn (Estonia) in the form of the Reval Dance of Death. Bernt Notke created this around 1500, based on his Dance of Death frieze in Lübeck. This fragment, also painted on canvas, depicts 13 figures and forms the beginning of what was originally a complete Dance of Death. The dynamism of the figures and the luminosity of its colours still give us an idea of how expressive the old painting in Lübeck must have been.

The delicate wall covering of the Lübeck frieze was repaired frequently over the years and was finally so worn by 1701 that the entire painting was replaced with a copy by the church painter Anton Wortmann. At the same time, the distinguished city poet Nathanael Schlott created a contemporary stylised new poem, which, like the old dance of death, was placed in the same spot below the figures. The new verses conveyed a changed understanding of death, for the Baroque longing for death supplanted the joie de vivre and fear of death and the Last Judgement that were characteristic of many figures in the late medieval work.

The Dance of Death at St Marien has continued to have an impact from its creation to the present day. This is evidenced by traditional and new forms of this art genre, especially when wars, epidemics and other catastrophes evoke feelings of fear and powerlessness in the face of overwhelming forces. It is precisely at such times that people seek and find expression for their existential mood in the Dance of Death.

The Lübeck Dance of Death was completely destroyed during the Second World War. Today, two more recent artistic interpretations in the Dance of Death Chapel keep the theme of death and the dance of death alive. These are the two towering Dance of Death windows by Alfred Mahlau on the north wall and the semicircular window by Markus Lüpertz above the north portal of the chapel.

Mahlau designed his work in 1956/57 in memory of the destroyed frieze. He was inspired by the old figures. As a memorial to the Second World War, he placed the dance of death above the burning houses and towers of the city of Lübeck. However, the painter interprets this catastrophic scenario in a comforting way, transforming it into a vision of peace; for he interprets the cradle child at the end of the dance of death as the Christ child in the manger, overcoming death and raising his right hand in a gesture of blessing. The message culminates in the words "GLORIA IN EXCELSIS DEO. AMEN" (Glory to God in the highest. Amen).

The window, designed by Lüpertz in 2002, combines familiar Christian symbols of death and resurrection: the fish as a symbol of Christ, the skull in conversation with the dove of peace, which holds a blooming red rose in its claws as a symbol of love and life, the blue jug with the water of life, the snail as a symbol of death and rebirth, and the seven torches of the Apocalypse, which herald the Last Judgement. Seen in this light, the stained glass window is not a vision of horror, but rather an interpretation of death that offers hope and comfort.

Literature:

The Dance of Death in St. Mary's Church in Lübeck and St. Nicholas' Church in Reval (Tallinn). Edition, commentary, interpretation, reception. Edited by Hartmut Freytag (Low German Studies 39), Cologne - Weimar - Vienna 1993.

Zens, The New Lübeck Dance of Death, edited by Galerie Peithner-Lichtenfels, Vienna [2003].

Death

By former Marienpastor Inga Meißner

For many adults, dealing with death and dying is one of the few remaining social taboos. We are very reluctant to talk about it. In many cases, not even our closest relatives know what we want for our end of life. The goal is to be young, dynamic and active for as long as possible. This is sometimes referred to as youth obsession. And current research suggests that this is becoming increasingly achievable. "Homo Deus" – it is conceivable that human decline and disease will be medically surmountable in a few decades. At the same time, the hospice movement and society's debate on issues such as living wills have set in motion a counter-movement. A movement that is very important:

When our loved ones know our wishes regarding the end of life, we enable them to feel reassured that everything will be taken care of according to our wishes when they say goodbye.

And yet there is still work to be done. What if death and dying themselves lost some of their terror? Because we have images of them that do not frighten us. Because we look beyond suffering to what we believe awaits us beyond the threshold of death. Just as J.K. Rowling has Albus Dumbledore say: "After all, death is just the next great adventure for the well-prepared mind." Here we can learn from children. And I find that very biblical: we should receive the kingdom of heaven like children. Children do not yet know that topics related to dying and death are social taboos. They express what is on their minds without filters or self-censorship. They divide their grief into portions that they can cope with. And so it can happen that one moment they are inconsolably crying over a loss, and the next moment they are happily playing again.

I would like to encourage us to do the following: to dare to learn something from children; to allow ourselves to be afraid; to allow ourselves to develop images of what comes after death; and to dare to exchange our own ideas and thoughts on this subject with those that people from the worlds of art and history have had over the centuries.

Life

By Marienpastor Robert Pfeifer

Where do I come from? Where am I going? How can I live? Since the 13th century, the Gothic Basilica of St. Mary has reflected in an unsurpassed way on fundamental questions of human existence. Questions that preoccupy people of every generation. The medieval, sublime processions in the cathedral's liturgical celebrations, the entrances in white robes with precious jewellery, the stylised rituals with their distancing habitus were given an artistic addition in the form of the democratisation of life's goal:

The dance of death depicts both the fear of the end and the perspective of equality for all.

With the Dance of Death, the cathedral unfolds a satirical vision of deep consolation that urges every life to take shape. What a design! One can imagine how the trembling believer entered the confessional chapel, the monumental wall frieze and thus the profound seriousness of the situation before his eyes – only to then be assured of the forgiveness of his sins. This meant nothing less than the continuation of life. The fascinosum et tremendum, as Rudolf Otto described it in perhaps the most significant religious studies project of the last century, "The Sacred," becomes apparent here.

Faith responds to life's ultimate questions first and foremost with respectful perception and interpretation of the reality of life – in order to admit that, as human beings, we can only ever tremble and allow ourselves to be comforted. Just as the Antwerp Altarpiece in St Marien shows us with its depiction of the death of Mary: a comforted death. Death as a transition to the other life, about which we know nothing and hope for nothing but peace.

In the midst of life, we are surrounded by death

At first glance, the dance of death seems creepy or even disturbing. But upon closer inspection and reading the texts, one becomes more thoughtful. And then suddenly: so incredibly grateful for these breaths that we call life.

Felix

Volunteer